| Contents > I’m a Bluesman : The role of perception in the construction of blues music by Andrew Pleffer |

| Page 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

I’m a Bluesman

The role of perception in the construction of blues music

I would like to investigate an idea that occupies a pivotal place in modern musicology – that of the ‘bluesman’. The ‘bluesman’ has adopted a central space in the musical tradition of blues – revealing more about those who perceive ‘him’ than the ‘bluesman’ himself. So much is this the case that the persona of the ‘bluesman’ possesses a mythical quality, one that also shapes perceptions of blues music.

A perception is more than just an observation (Martin, 1998: 287). A perception is a conversation, an interpretation of social signals and given understandings. What we perceive reveals more than just the objects around us; it reveals our connections in time and space. Investigating perceptions therefore requires us to understand ideas about the social and physical spaces by which we are surrounded and through which we are interpreted.

In all forms of visual media, a dominant perception of the ‘bluesman’ prevails. First and foremost, he is masculine and of African-American descent (see Figure 1.1). Preferably born in the Deep South sometime between 1880 and 1940, he is either old, or dead. He is a self-taught amateur, primitive and uneducated; a poor and lonesome itinerant musician, wielding his acoustic guitar everywhere he goes. The bluesman’s attire is almost strictly brimmed hat, suit and tie. He bears a triple-barrel name, occasionally from birth, but more commonly from a nickname or some other performance pseudonym – especially if he suffers from an ailment such as blindness (see Figure 1.2). Like an outlaw, he is untrustworthy, mysterious, potentially violent, and down-right mean. He is heterosexual and promiscuous, with his likes being women and whiskey (see Figure 1.3). Finally, he only ever plays the blues.

(from left to right) Figure 1.1 “Howlin’ Wolf”, by Owen Smith, in Rolling Stone Australia, Issue 642 (August 2005), p.46; Figure 1.2 “Blind Gary Davis”, by Robert Crumb, in R. Crumb's Heroes of Jazz Blues and Country, New York: Abrams, 2006, p.63; Figure 1.3 “T-Model Ford”, by Joe “Seeing Eye” Sacco, in The Rude Blues, Oxford: Fat Possum Records, 2000, p.3.

This perception of the bluesman represents a particular vision and articulation of a musical tradition. It “reflects a blues myth grounded in rhetorical narratives and visual tropes of poverty and primitiveness… packaging the music and its culture as a static historical object belonging to some bygone era” (King, 2006: 237). Interestingly, most, if not all, of the early twentieth-century musicians now labelled ‘bluesmen’ had vast repertoires that included some blues. Far from being “cut off from the currents of modern life” (Charters, 1959: 27-32), these musicians were proficient in a number of other styles (e.g. ragtime, spirituals, cowboy songs, cajun music, etc.) by listening avidly and attentively to radio and phonograph records (Wald, 2004: 96-101). Though this repertoire was shared by African-Americans and Caucasian-Americans, it became segregated due to record company policies that restricted and mythologised racist practices. Put simply: blues was for blacks; country for whites. So while blues music began with talented musicians it also began with racism, generally from the white recording industry’s construction of the bluesman “as a sign of Otherness” (Witek, 1988: 192).

The dominant perception of the bluesman shifts slightly here as we see him from another perspective – that of his cultural and political constraints. It was not the African-American bluesman who was responsible for the recording of blues and only blues, rather it was the early recording industry that was responsible for inventing the concept of the African-American bluesman (Dougan, 2001: 29; Evans, H., 2004: 56; Wald, 2004: 54-56). Mythologising blues music has removed these constraints from our vision and distorted our perception.

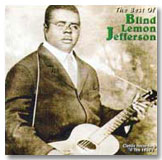

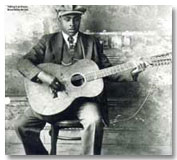

So who are some of these supposed ‘bluesmen’ and do they even fit the image? Observing the names and portraits of the following musicians seems to confirm this perception, in part: Blind Lemon Jefferson (Figure 2.1), Blind Willie McTell (Figure 2.2), Mississippi John Hurt, Sonny Boy Williamson (Figure 2.3), Mississippi Fred McDowell, and, John Lee Hooker. Consequently, this caricature appears everywhere in articles, books, paintings, and movies – especially in parodies.

(from left to right) Figure 2.1 “Blind Lemon Jefferson”, in Mojo Classic, “Eric Clapton and Blues Heroes” Issue (July 2005), p.141; Figure 2.2 “Blind Willie McTell”, in Mojo Classic, “Eric Clapton and Blues Heroes” Issue (July 2005), p.133; Figure 2.3 “Sonny Boy Williamson”, in Robert Johnson: The complete recordings, Columbia Records, 1990, p.13.

However, though it may prove a convincing characterisation, many scholars have recently produced research that seeks to revise the way we think about blues-related matters. Elijah Wald insists that “Our present-day idea of blues has largely been determined by people who had little if anything to do with the culture that produced the music” (2004: 7). Similarly, Howell Evans examines the various ways in which writing about blues music has altered our perceptions (2004: 53). He states that:

-

writing about the blues becomes a secondary system of representation that produces meaning in the first. This secondary system functions as myth. Blues critics have both created and relied on this secondary system of representation, this blues myth, to derive meaning from the blues. This myth of the blues consists of everything that has been said or written about the blues, including histories, documentaries, biographies, ethnographies and scholarship. Some of this blues writing has taken on a mythic quality… and some has quite literally taken the form of myth… (Evans, H., 2004: 43-44)

To paraphrase Roland Barthes (1957: 109), a myth is that which is spoken and communicated; it is a process of signification and shared perception, often one that goes without saying. What the shared perception of the bluesman reinforces is the myth of a poor, heterosexual, masculine, secular, promiscuous, African-American.

| Page 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Contents > I’m a Bluesman : The role of perception in the construction of blues music by Andrew Pleffer |